An ofrenda on Maribel Arredondo’s wall displays black and white photos of loved ones who died, their faces frozen in time. Crosses of various shapes and sizes highlight the Arredondo’s strong Catholic faith.

The floral scent of Fabuloso cleaner wafted through the whole house, a clear sign that the floors had just been mopped. Both of their daughters’ Quinceñera photos are displayed along their staircase.

Citlali Arredondo wore a blue dress, and her sister, Isabella, wore a yellow one.

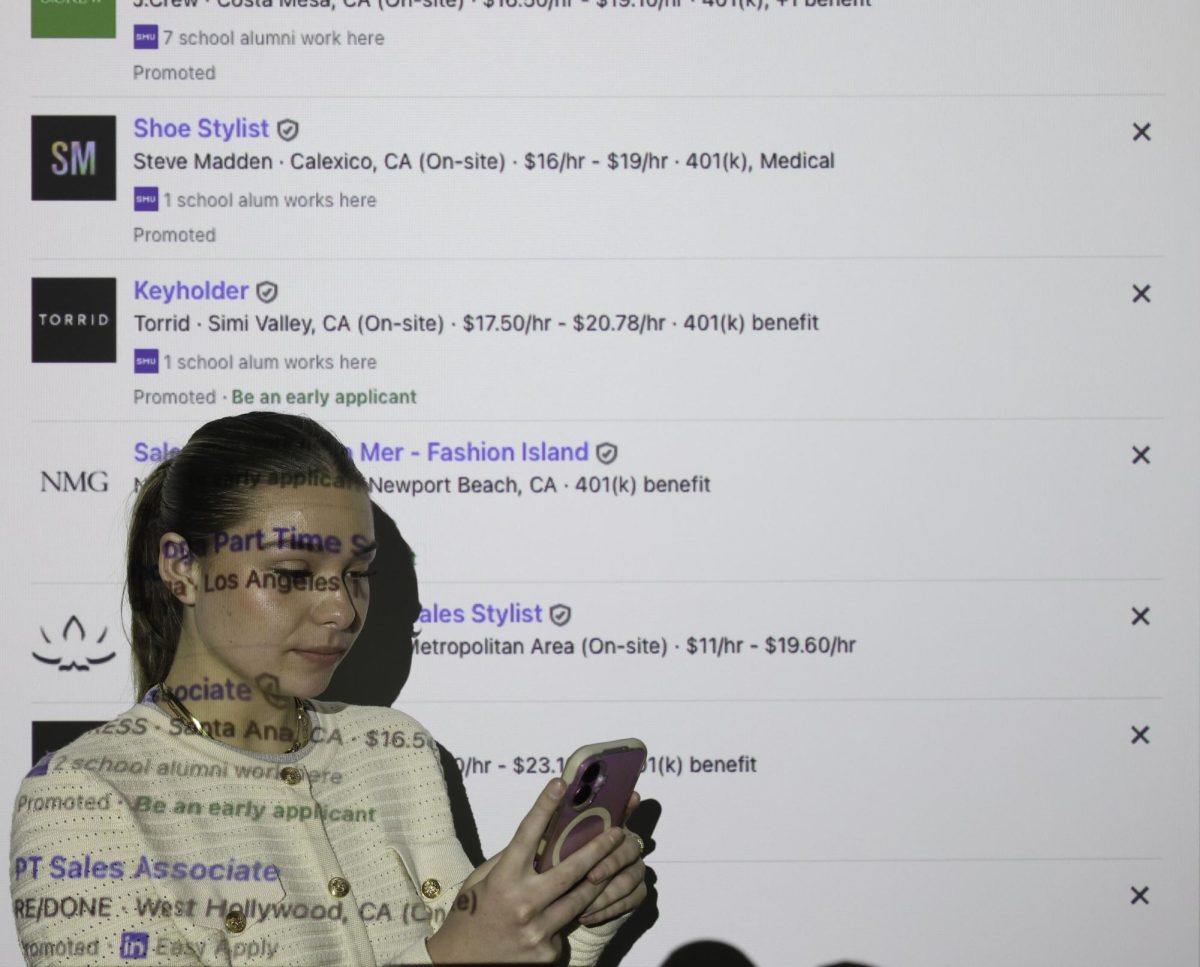

Citlali is now a 21-year-old SMU senior whose life has been shaped by the politics of the last nine years. A double major in political science and human rights, she said issues of immigration and civil rights have been a constant presence for not only her Mexican community, but her family. Her life has been shaped by the politics surrounding immigration.

“I’ve known since seventh grade that I was going to be an attorney,” Citlali said.

That was the first time Trump was president and pushed hard-line immigration policies such as building a border wall, separating children from parents who illegally crossed the U.S.-Mexico border, and enacting a short-lived Muslim ban. Citlali felt targeted because of the harsh messages towards immigrants like her parents, she said.

“I knew that I was going to do lots of mock trials, lots of pre-law work, but I think I did civil rights and human rights things due to being affected by those and seeing other people being affected by it,” Cetali said.

Her parents, Maribel and Jose Arredondo, who sit side by side on a tan leather couch, have been impacted by the U.S. immigration policy.

Maribel and Jose are homeowners, hard workers and in the U.S. legally. Though they’ve lived most of their lives in the U.S., they celebrate their Mexican roots and culture to honor their home country. However, the country that once provided them with the American Dream has turned against the Arredondos and countless others, pitting them against those who don’t understand the immigrant experience.

“‘Be a hard worker,’” Maribel said. “I think that’s instilled in us since we were little to always work hard, and that’s really what we’re known for as Mexicans.”

In October 2024, Jose Arredondo had a stroke. His speech is not the best, and at times, he is hard to understand. That has not stopped him from voicing his opinion on immigration and the discrimination that he has personally faced.

Maribel and Jose say it wasn’t a matter of choosing Mexico or America, but rather, the place their parents felt they could flourish.

For Maribel’s family, the year was 1977. At only 7 years old, Maribel’s single mother and five other siblings came to the U.S. after driving across the border. It wasn’t easy at first. Maribel said her mother recounted how she grew up during a time in Mexico when getting an education was difficult for women. Instead, women were encouraged to learn about household chores, such as cooking, sewing and cleaning. Her mother cleaned uniforms for anyone who needed them in their town of Nuevo Laredo.

“Things were just tough for her being a single mother with six kids,” Maribel said.

Jose said he doesn’t know much about his dad’s side of the family. His father left their family to work in the U.S. to ensure that Jose and his sister could one day join him in the States. At 12 years old, Jose emigrated to the United States.

“He came here for a better life, better work, better living overall, that’s why he came here,” Jose said.

As young children in the U.S., both Maribel and Jose experienced racism because neither of them spoke English.

Maribel said she remembers going to school and sitting behind a partition separate from the rest of her class. For six hours every day, she learned numbers, colors and letters, while the rest of her class learned subjects like math and reading. She wasn’t alone behind the partition either, she said.

“Everybody else knew that I didn’t speak English, and they knew the reason why I was behind the partition because the classroom was split, and behind the partition was everyone that didn’t speak English,” she said.

During class, Maribel said she remembers being asked to pronounce a word in English. Though Maribel knew the word, she didn’t want to say it.

“I remember knowing the answer, but I was too embarrassed to say it because I didn’t know if they were going to make fun of me,” Maribel said.

As a punishment, her teacher made Maribel stand in the corner while the teacher briefly stepped out of the classroom. Maribel’s classmates began to chant racist phrases at her.

“I remember the kids calling me a wetback,” she said. “‘You know, you’re there because you’re a wetback.’”

Maribel still remembers the kids who bullied her. She said even though all the children’s last names had some Hispanic roots, Maribel still felt different. Really, the only difference was that they spoke English and she couldn’t.

Jose also experienced racism in school for only speaking Spanish. When he started school in the U.S. in the seventh grade, he said he fought almost every week with six or seven boys because they would make fun of him for not knowing English.

“I didn’t speak, not even ‘Okay,’ not even ‘Hello,’” Jose said.

As of March 1, President Trump issued an executive order making English the official language of the U.S. The order reverses a 25-year-old rule that required federal agencies to help people who had limited English language skills.

Before Donald Trump ran for office, Maribel said she never experienced a president with such power in the U.S. come down so hard on immigrants. Now more than ever, she and her family feel there is a clear message for the Arredondos and the rest of the Hispanic community: if you are not from the U.S., you are an immigrant, you don’t belong here.

In this past election, 43% of Latinos voted for Trump. The Arredondo family did not vote for him.

By the end of his first day in office, Trump issued 10 executive orders relating to immigration. Some impacted the southern border, ending birthright citizenship for children born to undocumented immigrants and individuals with temporary status and suspending a 1980s-era refugee resettlement program. However, these orders did not take effect because federal courts blocked them.

These executive orders put many immigrant families in a state of fear, Maribel said. Bullying incidents have been reported in North Texas school districts among school children as young as 11 years old. In Gainesville, students reported harassment about comments made towards them about their families getting deported by ICE.

When Trump served his first term in office, Citlali said she and her sister Isabella saw school as an escape from what they heard about immigration on the news.

“There’s no way that what they are saying about us is true, because we know that we’re not criminals, our families aren’t criminals, our parents aren’t criminals,” she said.

Citlali’s positions in SMU student organizations now reflect the early experiences she had as a middle school student and as a college senior. She is an event coordinator for the Human Rights Council, an attorney for the Mock Trial team and the vice president of the Hilltop League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC).

Citlali is close friends with the president of Hilltop LULAC, Manuel Serrato De La Torre. De La Torre met Citlali when they both transferred to SMU. They quickly bonded over their Mexican-American heritage. Now, they are both seniors getting ready to graduate in December.

“Through LULAC, we share similar experiences, similar concerns, and also agendas on what we want to do politically,” De La Torre said. “Hopefully, in the future, we work as politicians, but also as attorneys.”

Many Mexican-Americans have a hard time identifying if they are Mexican or American. De La Torre has experienced that struggle, but having Citlali around, a person he described as his “partner in crime,” has only pushed him to continue fighting the ideas some people have about individuals of Hispanic descent.

Arredondo women find fulfillment and value in education. Citlali’s sister, Isabella, 19, studies kinesiology at TCU.

“Just like me, she was very academically driven,” Citlali said.

In addition to Citlali and Isabella, Maribel and Jose also have a son, Cristian, who works in the automotive industry.

When asked about seeing their children grow up in America, Jose emphasized the best part for him and Maribel.

“That’s easy,” Jose said. “Our girls going to college.”

As her husband spoke, Maribel’s eyes filled with tears, not out of sadness, but because Jose’s words reflected her feelings. With a slight crack in her voice, she recalled her excitement when Citlali received her first college acceptance letter from Louisiana State University.

“I jumped and hollered, and I was so happy that she got an offer because I always dreamed about that,” Maribel said.

When Citlali got accepted to SMU, Maribel remembered driving by the Dallas campus while she attended a secretarial trade school nearby. On days when she had extra time, Maribel would drive through SMU and see students walking on the lawn and going to the libraries, she said.

Citlali’s college acceptances meant Maribel finally got to see the work and struggles that her own mother went through come to fruition.

“I felt like my mom’s sacrifices were paying off,” Maribel said.

Maribel and Jose have never forgotten their experiences coming to the U.S.

Despite the racism they experienced because of their Hispanic background, the Arredondos feel it is important for their three children to be aware and proud of the roots and culture they come from. Whether it is cooking traditional Mexican meals, throwing each of their daughters a Quinceñera or naming their kids traditional Mexican names, they said there is always a reason to keep the culture alive.

“I’ve always felt very proud of who I am, and I wanted to bring that to my children,” Maribel said.